About Historical Trauma

Click image to enlarge

Each toolkit underscores the importance of cultural sensitivity in assessment and treatment and relies on the overarching conceptual framework for how historical trauma may impact an individual, families, social networks, and communities.

Historical trauma refers to complex and collective trauma experienced over time and across generations by a group of people who share an identity, affiliation, or circumstance. Originally introduced to describe the experiences of children of Holocaust survivors, the term historical trauma is now applied to multiple populations that have historically been marginalized within a society (see figure).

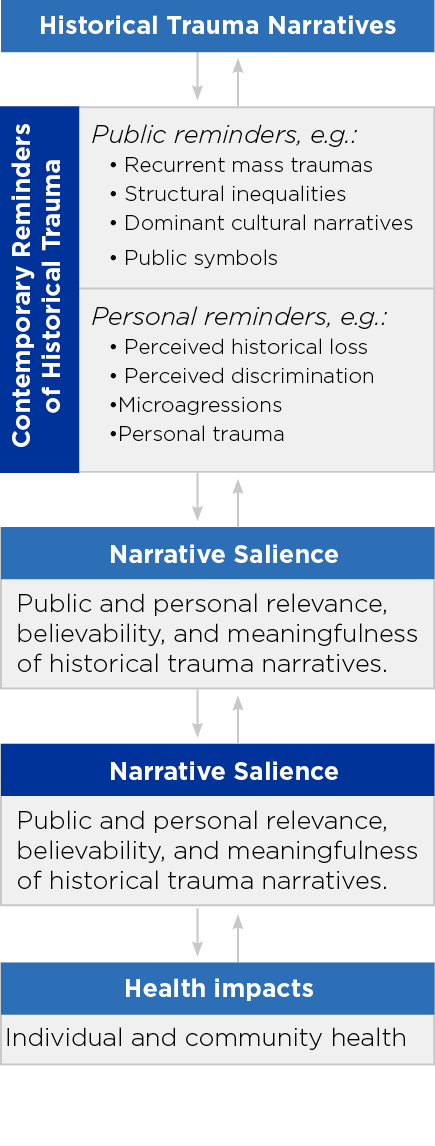

Figure 1 describes how historical trauma can influence the health of individuals and communities. It elucidates the origins of the distresses experienced by marginalized minority groups, and the relevance of this series of toolkits for them.

Within the U.S., populations with historical trauma include African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanics, Indigenous peoples, LGBTQ people, Muslims, undocumented immigrants, women, and Jewish Americans. In addition, an individual patient may experience multiple forms of historical trauma if their cultural identity intersects across several marginalized groups (for example, a Hispanic women who is LGBTQ may experience racism, sexism and homophobia).

Important Terms

- Historical Trauma Narratives: Stories of historical trauma—including oppression, injustices or disasters—experienced by a population.

- Contemporary Reminders of Historical Trauma: Ongoing reminders of past trauma in the form of publicly displayed photographs and symbols as well as contexts, systems, and societal structures and individually experienced discrimination, personal traumatic experiences, and microaggressions.

- Narrative Salience: The current relevance or impact of the historical trauma narrative on the individual and/or his/her community.

- Health Impacts: Historical traumas may lead to a range of adverse health outcomes, including risks for PTSD, symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- Microaggression: A term initially defined by Chester Pierce, MD, as an everyday, subtle, and nonverbal form of discrimination experienced by African Americans during the post-Jim Crow period. Today, the term is used to describe both verbal and nonverbal subtle forms of discrimination that can be experienced by any marginalized population.

Suggested Assessment and Treatment Recommendations for Marginalized Populations

- Use the DSM-5 to provide an assessment framework of an individual’s mental health, especially as it relates to sociocultural context and history.

- Perform a Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI). This set of 16 questions that providers may use to obtain culturally relevant information during a mental health assessment. This free instrument examines the impact of culture upon an individual’s clinical presentation. The CFI identifies four domains of assessments:

- Cultural definition of the problem

- Cultural perception of cause, context, and support

- Cultural factors affecting self-coping and past help seeking

- Cultural factors affecting current help seeking

- Consider using the CFI’s 12 supplementary modules to gain additional insights into specific patient groups. Modules exist for immigrants and refugees, children and adolescents, older adults and other special populations.

- Affirm the importance of cultural competency training for providers including (but not limited to) learning about implicit bias, microaggressions, trauma-informed care, and culturally sensitive treatment.

- Consider the cumulative and overlapping impact of historical trauma and microaggressions upon the mental health of people belonging to multiple marginalized populations, known as intersectionality.

- Emphasize self-care for all patients by encouraging healthy routines for sleep, diet, exercise, and social activities. Consider the role of self-affirmations, vicarious resilience, meditation, yoga, and other forms of traditional/alternative/or complementary care in mental health.

- Increase social supports for patients by engaging their family, social networks and community in their care, as appropriate.

- Stay abreast of current news and events, particularly those that may affect specific marginalized patient populations. At the same time, try to be mindful to avoid information overload, which may contribute to provider burnout.

- Work with religious/spiritual leaders to provide faith-based mental health care, as appropriate.

Resources

- Llorente M, ed. APA Council on Geriatric Psychiatry. Culture, Heritage, and Diversity in Older Adult Mental Health Care. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. 2019. https://www.appi.org/Culture_Heritage_and_Diversity_in_Older_Adult_Mental_Health_Care

- Lewis-Fernández R, Aggarwal NK, Hinton L, Hinton DE, and Kirmayer LJ, eds. DSM-5 Handbook on the Cultural Formulation Interview. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2016. https://www.appi.org/DSM-5_Handbook_on_the_Cultural_Formulation_Interview

- Lim RF, ed. Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2015. https://www.appi.org/Clinical_Manual_of_Cultural_Psychiatry_Second_Edition

- Narrow WE, First MB, Sirovatka PJ, and Regier DA, eds. Age and Gender Considerations in Psychiatric Diagnosis. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2007. https://www.appi.org/Age_and_Gender_Considerations_in_Psychiatric_Diagnosis

- Office of Minority Health’s National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS): This website provides multiple resources for tailoring health services to an individual's culture and language preferences, which can ultimately help reduce health disparities and increase health equity among all populations.

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network's Conversations on Historical Trauma: This three-part document series outlines how historical trauma has impacted American Indian, African American, Japanese American, and Jewish American children and families. The series describes how health services for children and families of these populations should take into account not only their personal trauma and present circumstances, but also the historical trauma of their community.