Not “Just a Teenage Girl in Her Twenties”: A New Approach to Human Development

At the turn of the 21st century, research by developmental scientist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett, Ph.D., led to his proposal of the term emerging adulthood to describe the interval from the end of compulsory high school to adulthood (ages 18-30). A new American Psychiatric Association publication, "Emerging Adulthood," authored by Karen J. Gilmore, M.D., and Pamela Meersand, Ph.D., of Columbia University builds on Arnett’s work, arguing for the value of distinguishing two phases within this period: early emerging adulthood/late adolescence (ages 18–23) and emerging adulthood proper (ages 24–30).

To get a better sense of the evolving developmental experience and cultural expectations for young people, APA recently talked with Drs. Gilmore and Meersand to discuss their evaluation of Arnett’s work, their views on the developmental process and challenges of this age group, and the changes in the meaning of adulthood.

Q: What does “emerging adulthood” consist of and how has the concept of adulthood changed over the past 30 years?

A: Arnett’s research combines late adolescence and early adulthood into the stage of emerging adulthood. Our work seeks to refine, not refute, Arnett’s conclusion. There are five features of emerging adulthood that have been agreed upon in the literature of developmental research psychology: role exploration, instability, self-focus, feeling in between, and wide-open possibilities. In the 20th century, five traditional social markers of adulthood (independent domicile, stable career path, marriage, parenthood, and financial independence) were also agreed upon, but in recent years, emerging adults have eschewed four out of the five, endorsing financial independence alone as an enduring indication of adulthood. For them, there are two psychological capacities that signify true adulthood: the ability to make one’s own decisions and the ability to take responsibility for them.

Q: Why have we seen a shift in society’s perception of adulthood?

A: There are many reasons for the delay in the assumption of adult roles: greater availability of educational opportunities for women, an increase in the quantity of jobs and career paths that require college degrees, technological advances in birth control that allow the postponement of parenthood, and more. In addition, data shows that the envisioned trajectory of high school to college to full-time employment – set by national policies like the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 – does not become reality for many young adults. Only 41% of students who enroll in an undergraduate program complete the program in four years; even those who do graduate may not know how to proceed and might even return to their childhood homes. The traditional pathways to adulthood are no longer clear, especially as rapid changes in our techno-informational culture continuously require new capacities and a new kind of flexibility. This trend has set the stage for the “increasing complexity of pathways through youth” that we are witnessing.

Q: What differentiates early emerging adulthood (or late adolescence) from late emerging adulthood? Why should they be considered separately?

A: Adults aged 18-24 are witnessing older 20-somethings taking more time than was traditionally allotted to make life decisions such as choosing a romantic partner or a career trajectory, and this encourages their own ongoing experimentation. They do not begin to feel the pressure of the future until roughly ages 24-29. (The average age of first marriage is 30 for men and 28 for women, according to the U.S. Census. Bureau.) Active role exploration, which may include a significant amount of risk behavior, continues during the 18-24 age range but tapers during the mid-to-late 20s. (Risk behavior includes the use of drugs, alcohol, and other addictive substances; driving while under the influence of drugs; cyberbullying; and more.) Unfortunately, the vast literature on emerging adulthood has consistently used late adolescents as the exemplars of emerging adulthood, because so many studies of “emerging adults” exclusively survey college students. This expedient research choice excludes both the “forgotten half” and late emerging adults. It is the latter group who begin to seriously grapple with their version of adulthood. Moreover, It is this older group that generated the phenomenon of “failure to launch.”

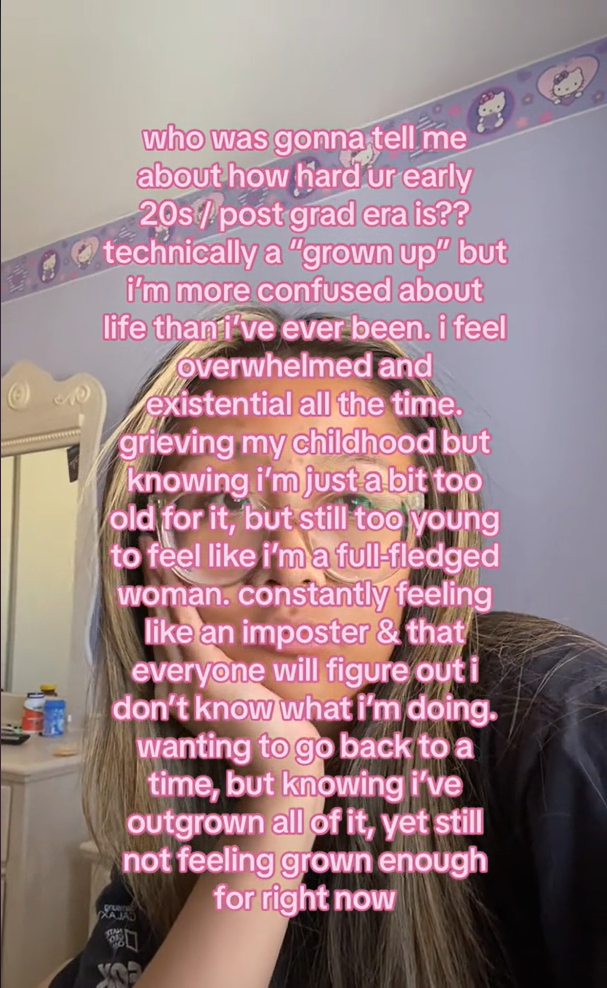

A recent Tik Tok post (left) from 20-something @herculeankate provides an example of emerging adults perspective: "who was gonna tell me about how hard ur early 20s/post grad era is?? Technically a “grown up” but I’m more confused about life than I’ve ever been. I feel overwhelmed and existential all the time. Grieving my childhood but knowing I’m just a bit too old for it, but still too young to feel like I’m a full-fledged woman. Constantly feeling like an imposter & that everyone will figure out I don’t know what I’m doing. wanting to go back to a time, but knowing i’ve outgrown all of it, yet still not feeling grown enough for right now"