Overtraining and Under Eating: Athletes at Risk of RED-S Syndrome

Katie Kirk grew up in an athletic family and she excelled at track and field, especially the 400-meter sprint. She was even one of the students chosen to light the 2012 Olympic flame in London. However, despite her continual success, she found herself having a compulsive need to train more and more and to restrict her diet to an extreme degree. She ran continously to achieve perfection and to be lighter and lighter. She isolated herself until she only interacted with her family, and she began to experience fatigue and repeated stress fractures. This led her parents to encourage her to see a sports doctor, where her slow recovery began.

Regular exercise typically improves mood, promotes better sleep, and prevents health problems such as high blood pressure. However, if people exercise too much, as Katie Kirk did, they can experience a wide range of negative health effects.

Regular exercise typically improves mood, promotes better sleep, and prevents health problems such as high blood pressure. However, if people exercise too much, as Katie Kirk did, they can experience a wide range of negative health effects.

When someone burns more calories than they eat, they have a relative energy deficiency. Relative energy deficiency can lead to a variety of health effects in athletes, and previously, these effects were understood as the female athlete triad: 1) menstrual problems, 2) weak bones, and 3) insufficient caloric intake.

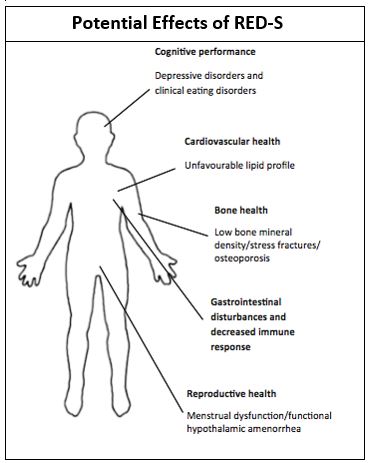

In 2014 the term “Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports,” or RED-S, was established by the International Olympic Committee, to identify the widespread effects of relative energy deficiency in both men and women. Unlike the female athlete triad, RED-S describes a wide variety of systems in the body that can be impacted by relative energy deficiency in all genders. These effects include menstrual dysfunction (typically cessation of regular menses, or getting menses less often than usual), poor bone health, problems with immunity, and poor cardiovascular health. The diagram shows some of the systems that can be effected. Athletes are at high risk for relative energy deficiency due to the increased risk for excessive exercise and disordered eating.

Many athletes do not meet criteria for an eating disorder, but do engage in harmful eating practices, such as fasting or avoiding certain types of food. Even if they are not trying to lose weight, nutritional deficiencies can develop as athletes try to eat “perfectly” for sport. Disordered eating is more common in athletes who play a sport that emphasizes appearance, leanness, or muscularity, such as track and field, gymnastics, rowing, or wrestling. These athletes are encouraged to lose weight, and often critiqued on their figures, which contributes to low self-esteem and disordered eating. It is estimated that disordered eating affects 62% of female athletes and 33% of male athletes.

Disordered eating contributes to relative energy deficiency, which can impact the athlete’s performance in a variety of ways. It can lead to an increased risk for injury, decreased coordination, decreased concentration, deceased muscle strength, irritability and depression.

There is limited information about the widespread effects of relative energy deficiency, especially in men. However, some symptoms for coaches, parents, and teammates to notice that could indicate a problem include:

- Frequent muscle sprain or fractures

- Slowed heart rate, more than expected

- Complaints of light-headedness, dizziness, or feeling cold

- Increased isolation, including isolation from coaches and teammates

- Prolonged or additional training above that required

- Unexpected weight loss (though this is not necessary for there to be a problem)

If you notice the above symptoms and/or have concerns for relative energy deficiency, disordered eating, or excessive training, it is recommended that you talk to the athlete in a caring and non-judgmental way and encourage them to see a doctor or a dietician. Other resources include their coach and athletic trainers and mental health services, including those available at most schools.

References

RED-S Image source: Logue, D., Madigan, S.M., Delahunt, E. et al. Sports Med (2018) 48: 73. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/10.1007/s40279-017-0790-3